Arts & Culture

A B A C A

Jing Ramos writes about how Francis Dravigny turned abaca into a high-profile luxury fabric.

Though the abaca resembles a banana plant, it is actually classified as hemp. Its scientific name is Musa textilis and is commonly known as Manila hemp ever since the Manila Galleon Trade in the sixteenth century.

Abaca also yields the highly sophisticated fabric t’nalak, handwoven by the T’bolis. The T’bolis are one of the early settlers in the untrammeled mountains of South Cotabato deep in the wilderness of Mindanao, the Philippines’ last outback. The T’bolis like certain aspects of their unique culture are a vanishing breed. They are however renowned as exceptional weavers and create an unusual tie-dyed cloth used locally for ropes, blankets and ceremonial robes.

In the T’boli community, abaca fiber is extracted from the mature, fruit-bearing wild banana plant. It takes two years for the abaca plant to mature. Utmost care is taken to preserve the length and silkiness in each fiber, as they are dried in the sun and stretched in a wooden frame that resembles an outsized comb whose teeth point up. Six trunks of the plant are needed to make fifteen meters of fabric. After the fiber has been neatly smoothened out, it is transferred to a bamboo frame unto which they are evenly and closely spread, one right next to the other, as in a backstrap loom. These are held evenly in place by a wooden bar in palm wood and laid directly across the fiber to be set later in an exact position in relation to the design.

Other than its natural cream state, the traditional colors woven in t’nalak are black and red for high contrast. The color combination works exceptionally well when set in the ikat process.

T’nalak weaving has long been a part of a tradition typical in a T’boli household and the weavers of this operation naturally comprise the female members of the community. The T’boli women involve themselves in a laborious system combining tie-dye technique with weaving. Whereas in other countries, tie-dyeing is done straight in a finished fabric, the t’nalak is dyed in individual threads. The process of weaving t’nalak among the T’bolis reflects their actual way of life.

That was abaca then, totally handcrafted, painstakingly slow and expensive to produce. The fibers were individually knotted and then dyed organically. To knot together one kilo of fiber required at least a week of intensive labor. It took almost two weeks in production to color the fibers, particularly the black which came from the leaves of the k’nalum tree, boiled and then steamed. It was said that the T’boli weavers dreamed the designs of their looms and often they themselves became temperamental in the process. The idea of imposing a deadline on the looms seemed almost impossible. Even the fibers tended to snap at midday when the temperature rose. The process of creating this cloth with its repetition of stylized animals or human designs requires absolute skill and patience. But once the finished products were washed, dried, waxed and pressed in cowrie shells, the results were often breath-taking and a touch luxurious. There is nothing quite like it until today.

Surprisingly after over fifteen years, designer Francis Dravigny developed the product mostly through research and consultation in Lyon, France, the center of the textile industry in Europe. The abaca has had evolved into a more contemporary vein. The looms are now much wider and the designer has added a few components to the fiber itself and although it is still hand woven, the cloth has a more industrial edge.

Surprisingly after over fifteen years, designer Francis Dravigny developed the product mostly through research and consultation in Lyon, France, the center of the textile industry in Europe. The abaca has had evolved into a more contemporary vein. The looms are now much wider and the designer has added a few components to the fiber itself and although it is still hand woven, the cloth has a more industrial edge.

The Lyon based designer has in fact opened Interlace, a manufacturing firm located in Mandaue, Cebu that caters to the international fabric market. In these private quarters is where the actual abaca looms are being produced.

The process of warping or vertical thread preparation entails two thousand thread strands for one loom set-up in which twenty one meters is the minimum length in a single loom. The whole process of warping requires a full day.

The second process is called the loom feeding, which has three underlying procedures namely the eye, reed and pulling process. The eye procedure needs two thousand thread strands for one loom set-up. Each strand is being fed to the first and the second eye. It is in the reed procedure where two thousand metal or stainless dents will be required for the two thousand thread strands processing. Three days are the maximum span of time to do both eye and reed feeding on the loom. Pulling is the third procedure of loom feeding wherein the two thousand thread strands will be divided by seven knots. Each knot will be pulled to straighten the warp and then tied to the wooden beam to give an even and stronger tension to the thread.

The final process is the horizontal weaving. Its basic components include a spooled tinagak and a wooden shuttle used to pass through the center of the warp. Upon reaching the other end of the loom, the weaver should swing the metal reed to compress the abaca in a repeated sequence. Then, the metallic reed is adjusted after every ten centimeters atop the loom to balance the thread. The wooden fabric should be rolled on the beam after every thirty centimeters to give tension to the fabric. In a day, the basic quota for every weaver reaches up to one and a half meters.

The final process is the horizontal weaving. Its basic components include a spooled tinagak and a wooden shuttle used to pass through the center of the warp. Upon reaching the other end of the loom, the weaver should swing the metal reed to compress the abaca in a repeated sequence. Then, the metallic reed is adjusted after every ten centimeters atop the loom to balance the thread. The wooden fabric should be rolled on the beam after every thirty centimeters to give tension to the fabric. In a day, the basic quota for every weaver reaches up to one and a half meters.

- by JING RAMOS photography Genesis Raña

Arts & Culture

Visayas Art Fair Year 5: Infinite Perspectives, Unbound Creativity

by Jing Ramos

This year’s Visayas Art Fair marks its 5th anniversary, celebrating the theme “Infinite Perspectives: Unbound Creativity.” The fair continues its mission of bridging creativity, culture, and community in the country. This milestone edition strengthens its partnership with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and expands collaborations with regional art organizations and collectives—reinforcing its role as a unifying platform for Philippine art.

VAF5 features the works of Gil Francis Maningo, honoring the mastery of his gold leaf technique on opulent portraits of the Visayan muse Carmela, reflecting spiritual awareness.

Gil Francis Maningo is celebrated for his gold leaf technique.

Gil Francis Maningo’s recurring theme of his Visayan muse “Carmela”.

Another featured artist is Danny Rayos del Sol, whose religious iconography of Marian-inspired portraits offers a profound meditation on the sacred and the sublime. This collaboration between two visual artists sparks a dialogue on the Visayan spirit of creativity and resilience. Titled “Pasinaya,” this dual showcase explores gold leaf as a medium of light and transcendence.

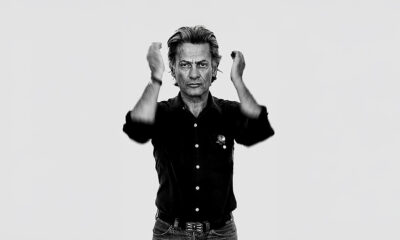

Artist Danny Reyes del Sol

Danny Reyes del Sol’s religious iconography.

Now in its fifth year, the Visayas Art Fair has influenced a community of artists, gallerists, brokers, collectors, museum curators, and art critics—constructing a narrative that shapes how we approach and understand the artist and his work. This combination of factors, destined for popular consumption, illustrates the ways in which art and current culture have found common ground in a milieu enriched by the promise of increased revenue and the growing value of artworks.

Laurie Boquiren, Chairman of the Visayas Art Fair, elaborates on the theme, expressing a vision that celebrates the boundless imagination of unique artistic voices:

“Infinite Perspectives speaks of the countless ways artists see, interpret, and transform the world around them—reminding us that creativity knows no single point of view. Unbound Creativity embodies freedom from convention and controlled expression, allowing every artist to explore and experiment without borders.”

Laurie Boquiren, Chairman of the Visayas Art Fair has tirelessly championed the creative arts for the past five years.

Arts & Culture

Kultura. Kapital. Kasalukuyan: Art that Speaks of Today

by Jose Carlos G. Campos, Board of Trustees National Museum of the Philippines

The National Museum of the Philippines (NMP) and the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) recently teamed up to prove that money isn’t just for counting—it’s also for curating! Their latest joint exhibition, Kultura. Kapital. Kasalukuyan: Contemporary Art from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Collection, is now open, and it’s a real treat for art lovers and culture buffs alike.

On display are gems from the BSP’s contemporary art collection, including masterpieces by National Artist Benedicto Cabrera (Bencab), along with works by Onib Olmedo, Brenda Fajardo, Antipas Delotavo, Edgar Talusan Fernandez, and many more. Some of the artists even showed up in person—Charlie Co, Junyee, Imelda Cajipe-Endaya, Demi Padua, Joey Cobcobo, Leonard Aguinaldo, Gerardo Tan, Melvin Culaba—while others sent their family representatives, like Mayumi Habulan and Jeudi Garibay. Talk about art running in the family!

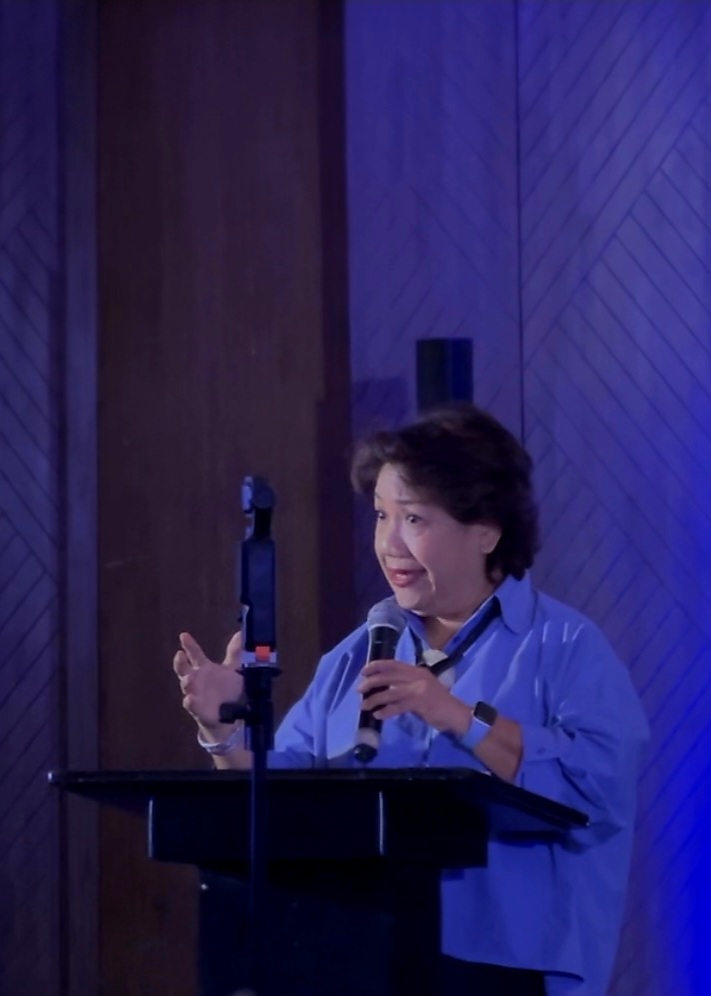

Deputy Governor General of the BSP, Berna Romulo Puyat

Chairman of NMP, Andoni Aboitiz

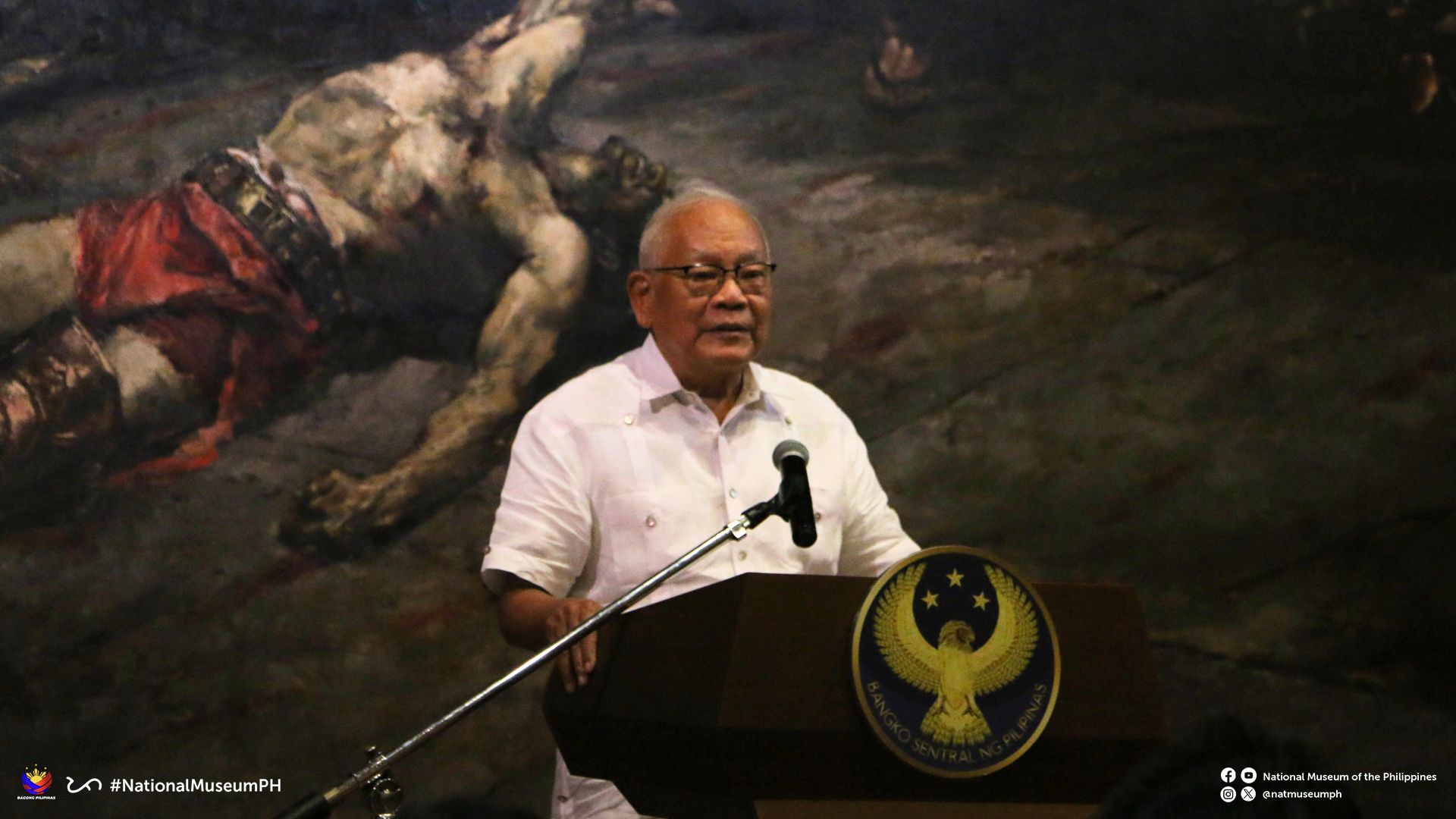

The BSP Governor Eli M. Remolona, Jr. and members of the Monetary Board joined the event, alongside former BSP Governor Amando M. Tetangco, Jr., Ms. Tess Espenilla (wife of the late Nestor A. Espenilla, Jr.), and the ever-graceful former Central Bank Governor Jaime C. Laya, who gave a short but enlightening talk about the BSP art collection.

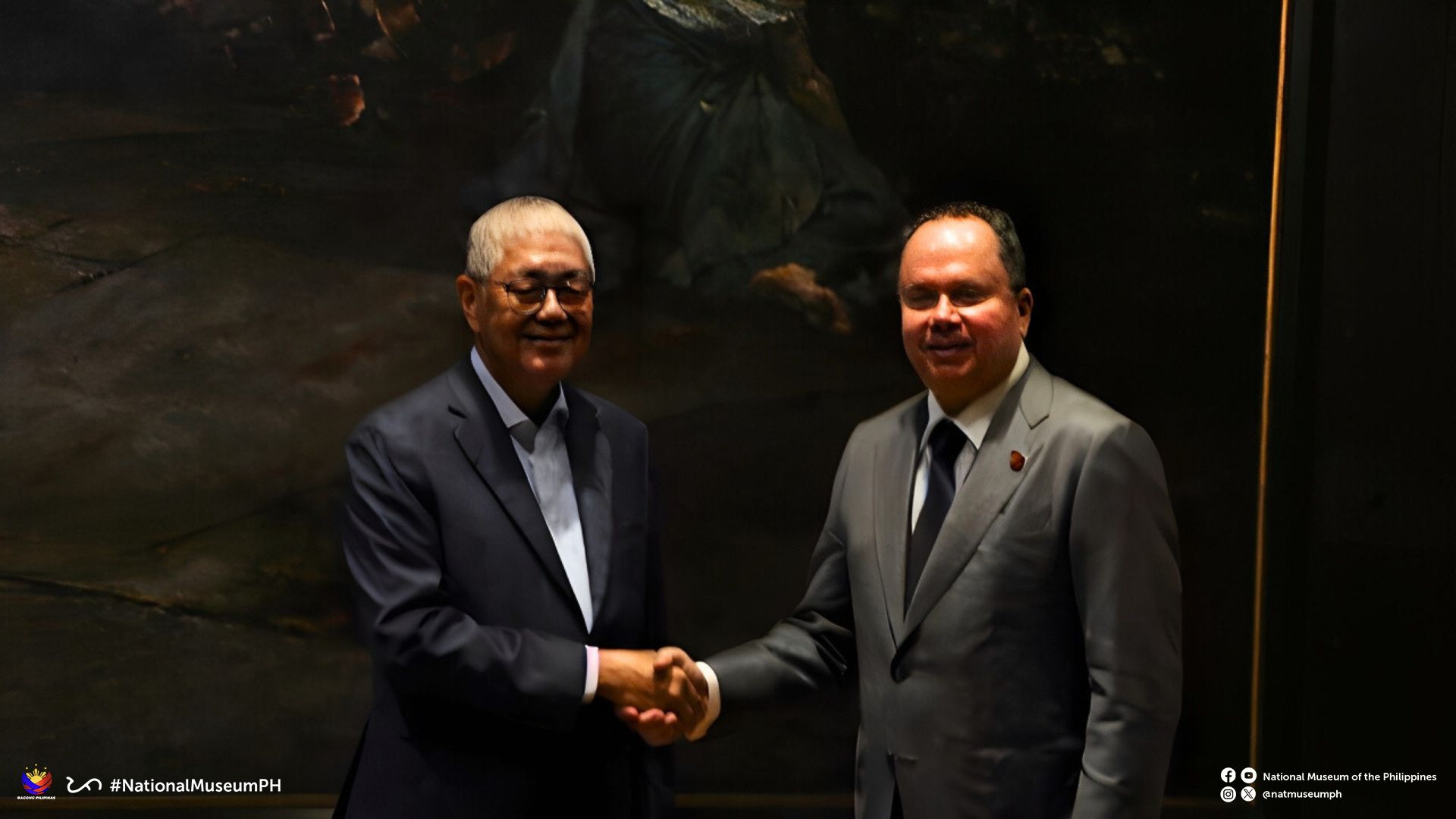

From the NMP, Chairman Andoni Aboitiz, Director-General Jeremy Barns, and fellow trustees NCCA Chairman Victorino Mapa Manalo, Carlo Ebeo, and Jose Carlos Garcia-Campos also graced the occasion. Chairman Aboitiz expressed gratitude to the BSP for renewing its partnership, calling the exhibition a shining example of how financial institutions can also enrich our cultural wealth.

Former Governor of BSP Jaime Laya

Governor of BSP Eli M. Remona and Chairman of NMP Board Andoni Aboitiz

Artist Charlie Co

Before the official launch, a special media preview was held on 5 August, hosted by BSP Deputy Governor Bernadette Romulo-Puyat and DG Jeremy Barns. It gave lucky guests a sneak peek at the collection—because sometimes, even art likes to play “hard to get.”

The exhibition Kultura. Kapital. Kasalukuyan will run until November 2027 at Galleries XVIII and XIX, 3/F, National Museum of Fine Arts. Doors are open daily, 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM. So if you’re looking for something enriching that won’t hurt your wallet (admission is free!), this is your sign to visit. After all, the best kind of interest is cultural interest.

Monetary Board of the BSP, Walter C. Wassmer

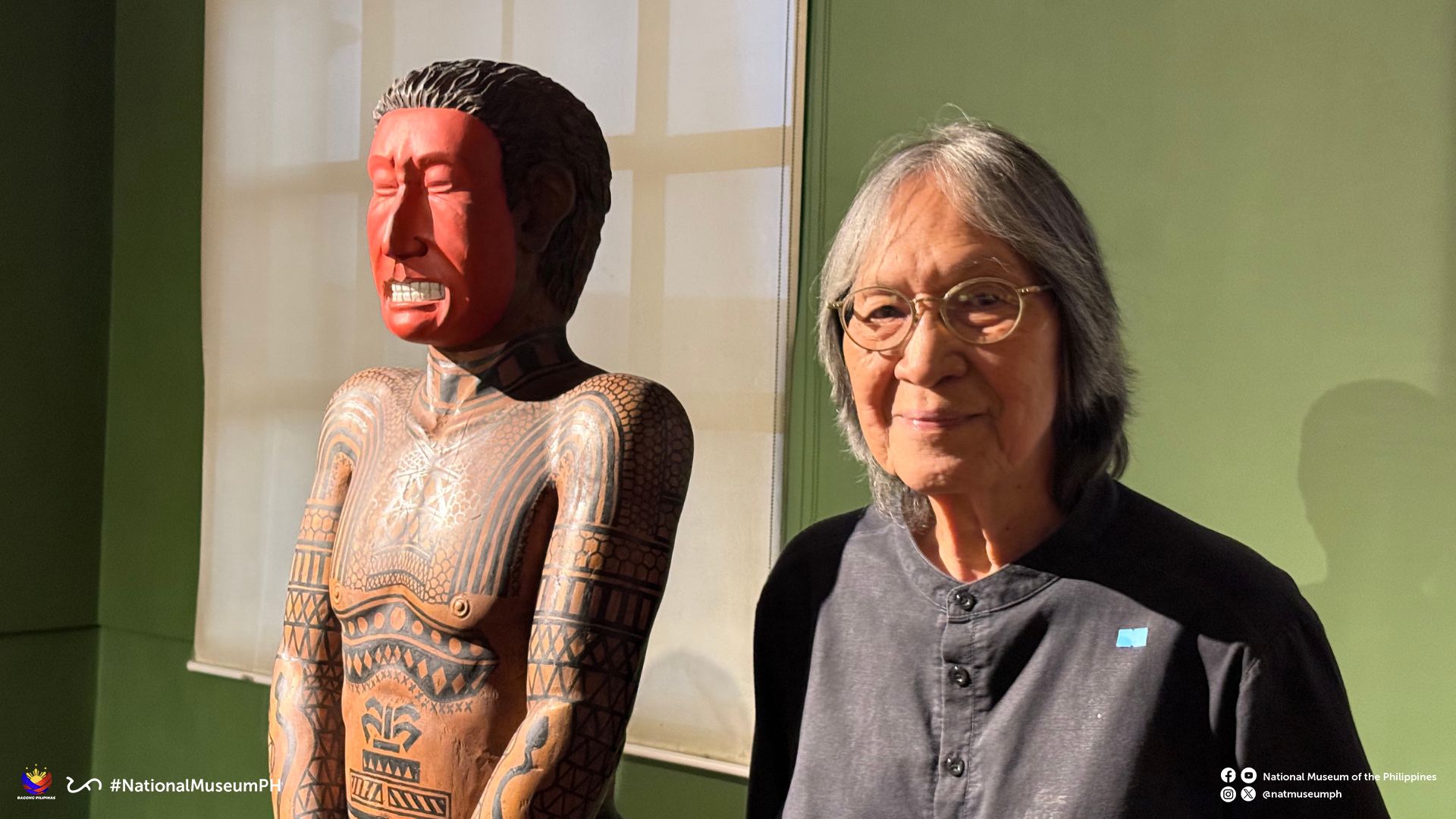

Luis Yee, Jr. aka ‘Junyee’ The Artist beside his Sculpture

Arvin Manuel Villalon, Acting Deputy Director General for Museums, NMP with Ms. Daphne Osena Paez

Arts & Culture

Asia’s Fashion Czar I Knew as Tito Pitoy; Remembrance of a Friendship Beyond Fashion with Designer Jose R. Moreno

by Jose Carlos G. Campos, Board of Trustees National Museum of the Philippines

My childhood encounter with the famous Pitoy Moreno happened when I was eight years old. My maternal grandmother, Leonila D. Garcia, the former First Lady of the Philippines, and my mother, Linda G. Campos, along with my Dimataga aunts, brought me to his legendary atelier on General Malvar Street in Malate, Manila. These were the unhurried years of the 1970s.

As we approached the atelier, I was enchanted by its fine appointments. The cerulean blue and canary yellow striped canopies shaded tall bay windows draped in fine lace—no signage needed, the designer’s elegance spoke for itself. Inside, we were led to a hallway adorned with Art Deco wooden filigree, and there was Pitoy Moreno himself waiting with open arms—”Kamusta na, Inday and Baby Linda,” as he fondly called Lola and Mommy.

“Ahhh Pitoy, it’s been a while,” Lola spoke with joy.

“Oh eto, may kasal na naman,” my mom teasingly smiled.

Linda Garcia Campos and Pitoy Moreno’s friendship started when they were students in the University of the Philippines in Diliman.

When Dame Margot Fonteyn came for a visit to Manila, Pitoy Moreno dressed her up for an occasion.

We had entered a world of beauty—porcelain figurines, ancient earthenware and pre-colonial relics. It was like stepping into a looking glass, only Pitoy could have imagined.

Destiny led me back years later when my mother Linda told me that Pitoy Moreno was working on his second book, Philippine Costume, and needed research material and editorial advice. At this point, around the 1990s, I was in between assignments—unsure of how a broadcasting graduate like me could possibly contribute to a fashion icon’s masterpiece. Fortunately, I agreed to the project.

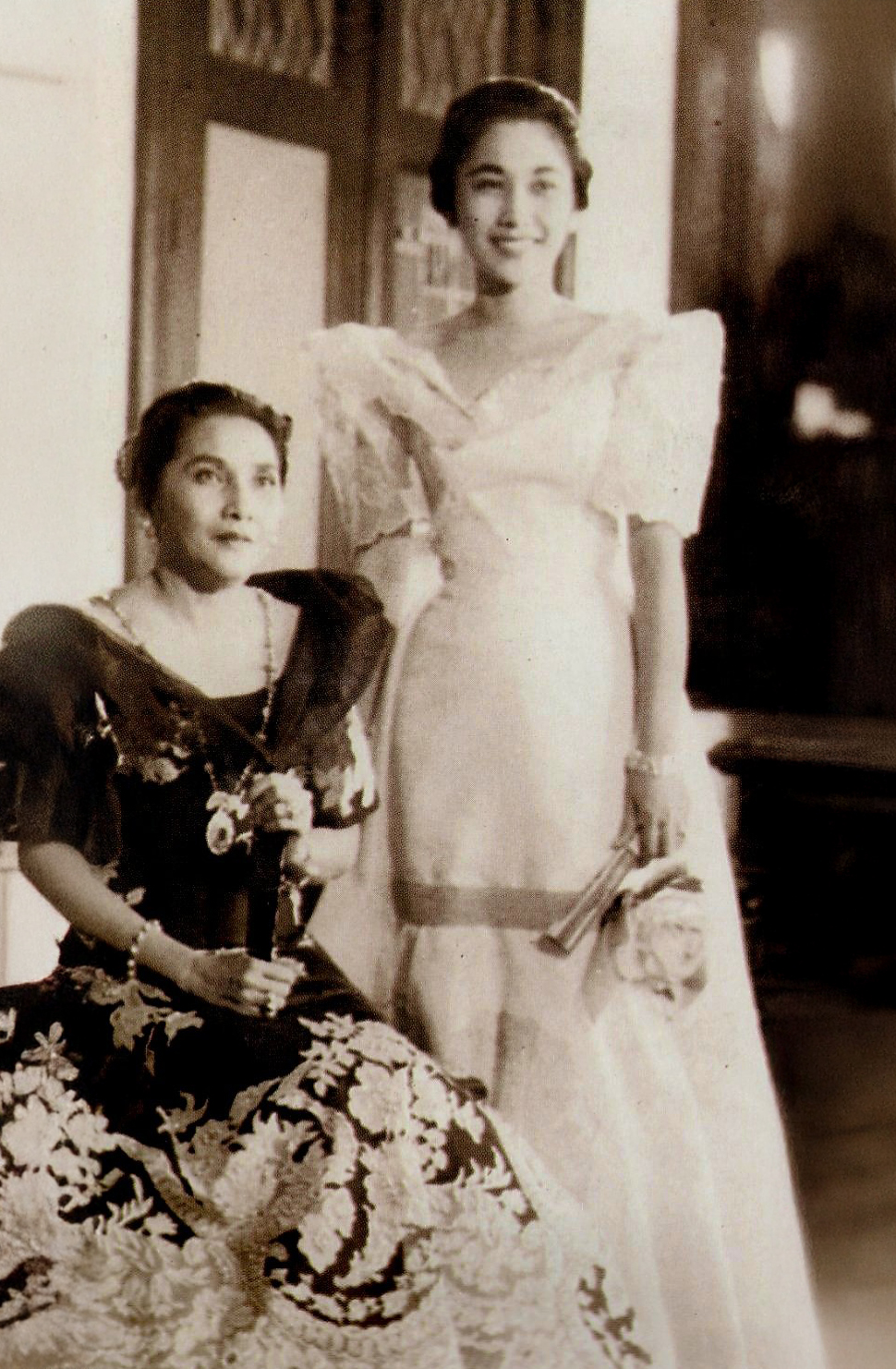

Former First Lady Leonila D. Garcia and daughter Linda G. Campos in Malacañang Palace.

Returning to the designer’s atelier brought back a rush of pleasant memories. The gate opened, and there stood Pitoy Moreno, beaming as always.

“Come in, hijo. Let me show you what I have in mind—and call me Tito Pitoy, okay?”

He led me to his worktable.

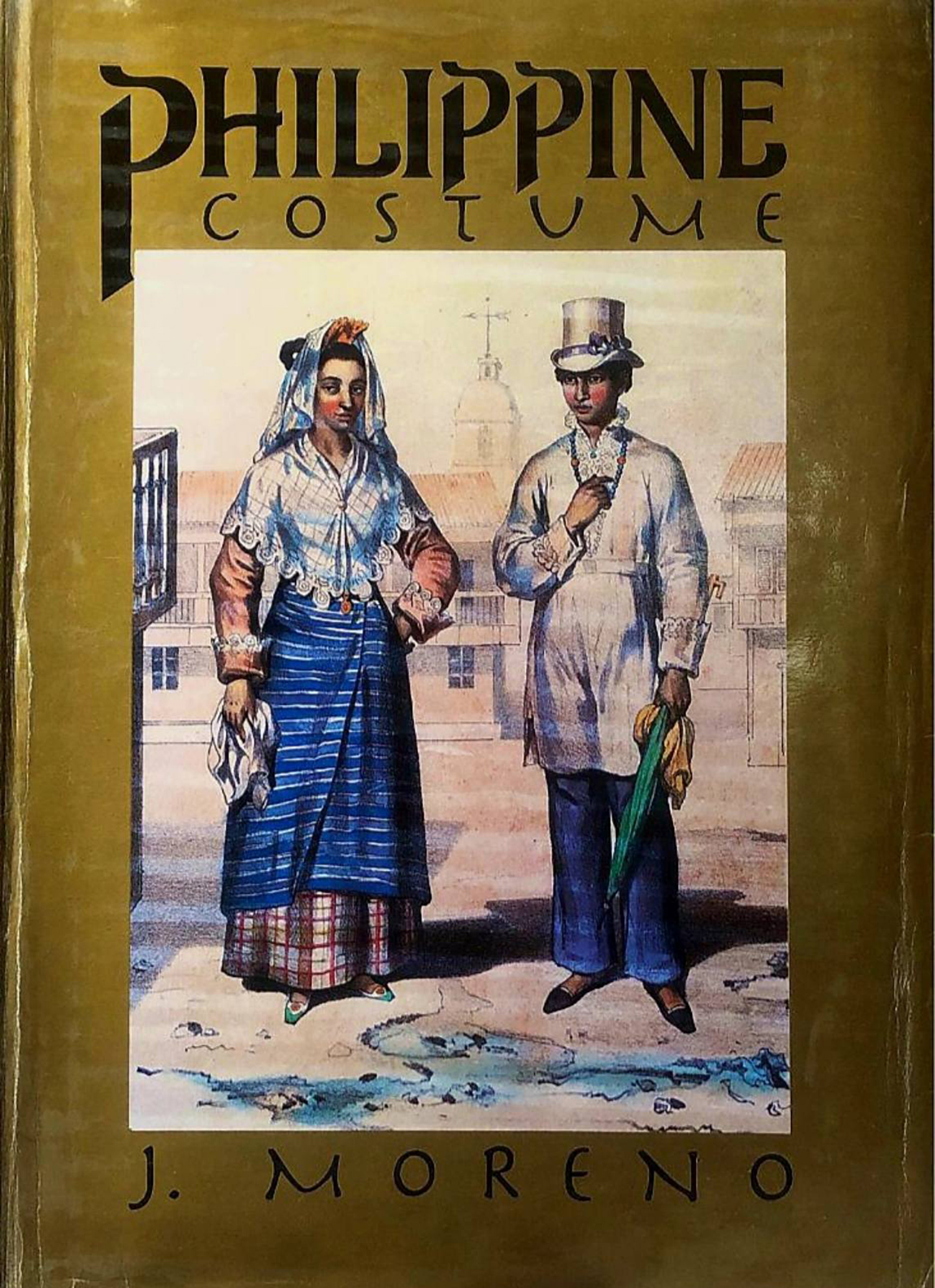

“I want to publish a book that tells the story of Philippine fashion—from our pre-colonial roots to the present. A designer’s collection of images and heritage expressed in clothing.”

I was awestruck. “How can I help you?” I inquired.

“Did you know that your mother, Linda, was my barkada in the University of the Philippines in Diliman?” he grinned.

US President Dwight Eisenhower with First Lady Leonila Garcia and President Carlos Garcia in a state dinner at Malacañang Palace in Manila.

That friendship soon led to one of the proudest moments of the designer’s life. He had the opportunity to dress not only the First Lady Leonila D. Garcia but also President Carlos P. Garcia during his term. It was also during this time that the President of the United States, Dwight Eisenhower, came for an official visit to Manila. The designer was able to make clothes for the President, his daughter, and his staff.

“Eisenhower even asked for discounts on the barong Tagalog,” Tito Pitoy laughed.

Tito Pitoy then asked if I could find a terno he had made for my Lola, the former First Lady, which she wore for President Eisenhower’s state visit in 1960.

“How about her other ternos, dated from the 1920s to the 1960s?” I offered.

He lit up.

I scoured my Lola’s extensive closet—it felt like unearthing a legacy. Tucked behind layers of vintage ternos from countless fashion designers, I found that terno, which was photographed by Dick Baldovino along with other pieces for the book project. Once the project was finished and I myself had moved on, my bond with Tito Pitoy never wavered.

When my Lola passed away, he was deeply touched when I personally informed him of the sad news. Once, at the wake of former Vice President Salvador Laurel, he asked me to assist him in the placement of the medals in the chapel.

Philippine Costume by Jose Moreno is the designer’s collection of images and heritage expressed in clothing.

Tito Pitoy later invited me to his 80th birthday celebration—a dazzling Manila affair in 2012. During the evening’s festivities, he handed me a printed copy of Philippine Costume and added warmly,

“Thank you, hijo. I’ll call on you for the next one.”

The highlight of his career—and his most unforgettable moment—came during the Metro Magazine Gala fashion show: A Tribute to Pitoy Moreno, Fashion Icon. A collection of evening gowns spanning six decades—many of them unseen and tucked away in his atelier—were revealed that night. When the finale came, Tito Pitoy walked the stage, triumphant and waving to a sea of admirers. Longtime friends from the industry, society’s finest, and fashionistas rose from their seats and gave him a standing ovation.

It wasn’t just to celebrate his craft and ingenuity—it was to honor the man who brought elegance, history, and heart in every stitch.

-

Prime Target2 months ago

Prime Target2 months agoBee Urgello–Fashion Influencer and Designer’s Muse Goes on a Hiatus

-

Fashion1 month ago

Fashion1 month agoCloud Dancer: The Resonant Reset of 2026

-

Travel1 month ago

Travel1 month agoSunlight in Siquijor: Discovering the Landscape Shifts and Coastal Plains of this Mystical Island

-

Travel3 months ago

Travel3 months agoAutumn in Istanbul: Fellow Travellers Share Turkish Delights

-

The Scene3 months ago

The Scene3 months agoBe Fabulous: Dr. Fremont Base’s 50th Birthday Party Echoes the Disco-Glam Era

-

QuickFx2 months ago

QuickFx2 months agoIn Black and White: Photographer Richard Avedon Captures the Cultural Zeitgeist of His Era

-

Prime Target4 weeks ago

Prime Target4 weeks agoRod Malanao: Empowering the Growth of the Luxury Fashion Industry to Designing Knit Wear on the Side

-

QuickFx2 weeks ago

QuickFx2 weeks agoBright Young Things: Why Cecil Beaton Remains Vital in the World of Photography

You must be logged in to post a comment Login