Arts & Culture

Santonilyo: The Pagan Origins of Santo Nino

Santonilyo was said to be an old and a new god to the pantheon of ancient Visayas. In relation to this, it was also believed that this was also connected to the Santo Nino de Cebu.

In Cebu, some, if not most, establishments or residences have always kept an altar or a pedestal with a carved wooden statue of a little king, clothed in rich fabric of red or green, wearing a golden necklace and bearing a scepter and a globus cruciger in his hands. This figure was brought by the Spaniards and is known as Santo Niño. This image is revered by Cebuanos, holding festivities in honor of the miraculous child Jesus.

During the pre-Spanish colonial era, our ancestors had similar wooden idols named as guardians, protectors and pagan deities. This brought a similar legend about a piece of drift wood that turned out to be miraculous, and scared away creatures when placed on the farms. Let’s take a look at the origins of the religious image that once was said to be a pagan god and converted to the catholic path to many of us believe in.

Ifugao “Bulul” Pair Rice God Statue with Inlaid bead eyes considered as a Lianito credits to www.tribalasia.com

The Lianito Idol

The Animist people of the Visayas region worshipped a time god known as Kaptan, equivalent to the creator god Bathala of the Tagalogs. He was the supreme deity in the Visayan pantheon, but relatively distant. To bridge the gap of the activities of heaven and the mortals, the ancient people replaced mediators such nature-based deities known as diwatas (fairies and elementals) and anitos (ancestral spirits) who supposed to give blessings and abundance on a family or a society.

Furthermore, these “Anito” spirits are usually old ancestors who have lived a virtuous life when they were alive. Each house in the ancient Visayas was supposed to carry a “tawu tawu”(idols) made out of wood, stone, gold or ivory whom the family pay honor in resemblance of offering food or flowers and “pag-anito”(worship) to ensure and continue daily blessings upon them. When the head of a family dies, everyone in the village help make the statue, they would carve out an androgynous (to further symbolize gender-equality), child-like image, and always smiling to what they would call the “Lianito”, the collective embodiment of the ancestor spirit of a family and territory and they would dress the doll with gold and would place the image among the other idols.

Painting of Queen Juana (Hara Humamay) by Filipino artist Manuel Panares

The Baptism

The birth of Catholicism in Cebu was through the image of Santo Niño de Cebu, brought by the Spanish Occupation through Antonio Pigafetta, an Italian scribe of Ferdinand Magellan, given as a gift to Hara Humamay the royal consort of the chieftain of Cebu of 1521, Rajah Humabon, as token of good relations and allegiance to Spain. The queen was baptized to Catholicism and renounced her animist beliefs and dubbed a new Christian name, “Juana”.

Queen Juana loved the image so much that according to the account of Pigafetta upon receiving, she bathed the statue with her tears of joy as she is hugging it. Eight hundred Cebuanos were baptized as well and were given an image of the Virgin Mary, a crucifix and a bust depiction of Jesus before Pontius Pilate. The Spaniards underestimated the animist faith that Magellan discovered that the king and queen still keep their Lianitos. The queen perhaps readily accepted the Santo Niño because it looked more regal and refined. Rest of the history follows of another chieftain’s refusal of conquering the land and instilling tradition that was Datu Lapu-Lapu and had a violent conflict which caused Magellan’s death.

Moving on its dark past of the conquest through religion, 44 years after Magellan came Miguel Lopez De Legazpi, arrived Cebu and found the native’s hostility and fearing the retribution for Magellan’s death. The villages were burned during the progressing conflict. Juan Camus, a Spanish mariner found the image of the Santo Nino in a pine box amidst the ruins of a burned-down hut. Presented the image to Legazpi and the Augustinian priests; the natives denied the gift was associated to Magellan and claimed it have been there for a long time. A church was built on the spot to where the image was found that was originally in bamboo and mangrove palms then was reconstructed later and claims to be the oldest parish in the Philippines.

The Youthful Deity of the Rain

Visayan natives submerse the Santo Nino image to venerate with and call out for the rain.

Filipino Historian Nico Marquez Joaquin’s workes in 1980 state that it was also within the time gap of those 44 years since Magellan that the natives discovered a new god in the pantheon of the Visayas. The new deity in the form of a child they call Santonilyo. Influenced in its Spanish title, they recognized the statue as a lianito describing both an old and a new god to the Visayans.

Santonilyo is the child deity of good graces who was worshiped as a rain god for four decades since the Spanish first arrived. Fray Gaspar de San Agustin wrote about it in 1565 book “Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas”, that during drought, the ancient Cebuanos would bathe the image in the sea.

“Cun ulan ang pangayoon, ug imong pagadugayon. Dadad-on ca sa baybayon, ug sa dagat pasalomon. Ug dayon nila macuha ang guitinguha.”

Which translates: “If they seek rain and you delay it, you’d be brought to the shore and bathed in the sea. They then obtain the rain they desire.” The practice of immersing the sacred image is also mentioned in the Sto. Niño’s Gozos (prayer hymn) published in an 1888 novena.

However, Santonilyo’s popularity was already widespread among the Visayan islands reaching the Panay, Mindoro, Negros, Bohol, Siquijor, Samar and Leyte. The Santonilyo as mentioned by Felipe Landa Jocano, an anthropologist and author of “Filipino Value System”, as one of the supporting Upper world deities along with Ribung Linti (god of thunder and lightning) who assisted Tungkung Langit (the creator god of Panay Islands) in the creation myth known as the “Sulod” Epics.

In its connection of the legend of Panay that Santonilyo was said to have reached the islands as a fisherman caught a piece of “agipo” (or a driftwood) but couldn’t catch fish the whole day. Dismayed, he threw it back soon after, felt another tug to his net and realized it’s the same driftwood and over and over again would dump it on the sea, known only to catch the same agipo again.

Tired and frustrated, the fisherman decided to keep the driftwood in his boat, and like a miracle, fish flocked towards his boat and returned to the village with a bountiful catch. The villagers soon discovered that the piece of wood had other magical powers used as a scarecrow to keep the birds and animals away in drying the grains and in times of drought, only had to immerse the driftwood in the sea to produce rains.

This agipo became an idol in their pantheon, and like the venerated Holy Child, Santonilyo is also prayed for graces. The Lianito idol then on was called Lisantonilyo. As Santo Nino has been honored and prayed in Cebu, we are able to peak in the origins of our faith based on discovery and documents not diminishing the fact on what we truly believe in which is God represented as a sweet, youthful child that would save the whole world from sin.

Arts & Culture

Visayas Art Fair Year 5: Infinite Perspectives, Unbound Creativity

by Jing Ramos

This year’s Visayas Art Fair marks its 5th anniversary, celebrating the theme “Infinite Perspectives: Unbound Creativity.” The fair continues its mission of bridging creativity, culture, and community in the country. This milestone edition strengthens its partnership with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and expands collaborations with regional art organizations and collectives—reinforcing its role as a unifying platform for Philippine art.

VAF5 features the works of Gil Francis Maningo, honoring the mastery of his gold leaf technique on opulent portraits of the Visayan muse Carmela, reflecting spiritual awareness.

Gil Francis Maningo is celebrated for his gold leaf technique.

Gil Francis Maningo’s recurring theme of his Visayan muse “Carmela”.

Another featured artist is Danny Rayos del Sol, whose religious iconography of Marian-inspired portraits offers a profound meditation on the sacred and the sublime. This collaboration between two visual artists sparks a dialogue on the Visayan spirit of creativity and resilience. Titled “Pasinaya,” this dual showcase explores gold leaf as a medium of light and transcendence.

Artist Danny Reyes del Sol

Danny Reyes del Sol’s religious iconography.

Now in its fifth year, the Visayas Art Fair has influenced a community of artists, gallerists, brokers, collectors, museum curators, and art critics—constructing a narrative that shapes how we approach and understand the artist and his work. This combination of factors, destined for popular consumption, illustrates the ways in which art and current culture have found common ground in a milieu enriched by the promise of increased revenue and the growing value of artworks.

Laurie Boquiren, Chairman of the Visayas Art Fair, elaborates on the theme, expressing a vision that celebrates the boundless imagination of unique artistic voices:

“Infinite Perspectives speaks of the countless ways artists see, interpret, and transform the world around them—reminding us that creativity knows no single point of view. Unbound Creativity embodies freedom from convention and controlled expression, allowing every artist to explore and experiment without borders.”

Laurie Boquiren, Chairman of the Visayas Art Fair has tirelessly championed the creative arts for the past five years.

Arts & Culture

Kultura. Kapital. Kasalukuyan: Art that Speaks of Today

by Jose Carlos G. Campos, Board of Trustees National Museum of the Philippines

The National Museum of the Philippines (NMP) and the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) recently teamed up to prove that money isn’t just for counting—it’s also for curating! Their latest joint exhibition, Kultura. Kapital. Kasalukuyan: Contemporary Art from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Collection, is now open, and it’s a real treat for art lovers and culture buffs alike.

On display are gems from the BSP’s contemporary art collection, including masterpieces by National Artist Benedicto Cabrera (Bencab), along with works by Onib Olmedo, Brenda Fajardo, Antipas Delotavo, Edgar Talusan Fernandez, and many more. Some of the artists even showed up in person—Charlie Co, Junyee, Imelda Cajipe-Endaya, Demi Padua, Joey Cobcobo, Leonard Aguinaldo, Gerardo Tan, Melvin Culaba—while others sent their family representatives, like Mayumi Habulan and Jeudi Garibay. Talk about art running in the family!

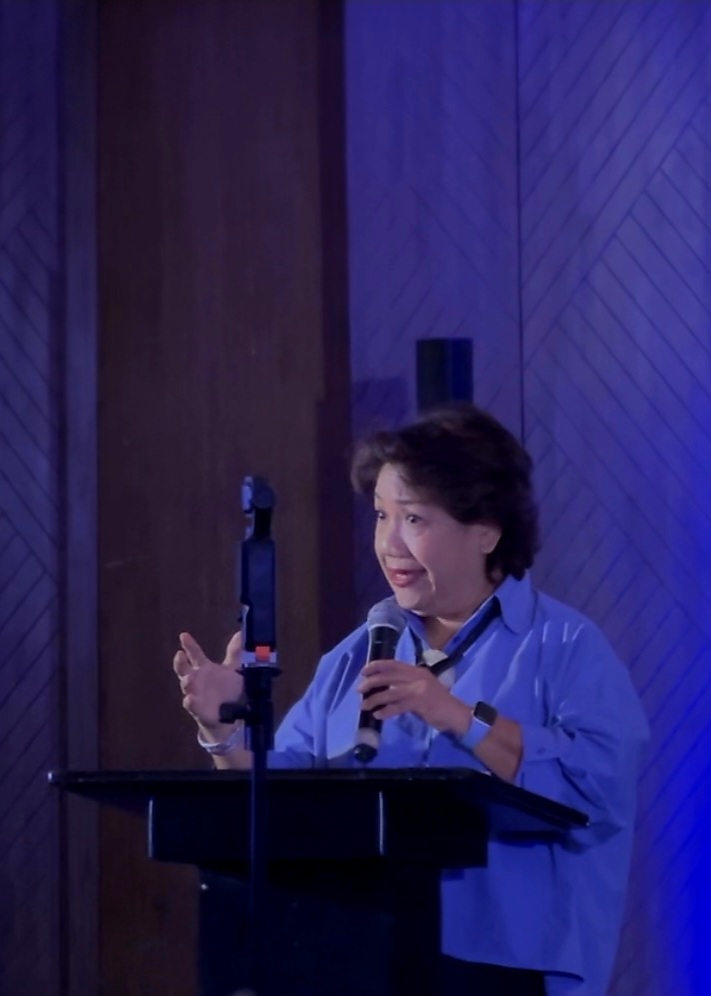

Deputy Governor General of the BSP, Berna Romulo Puyat

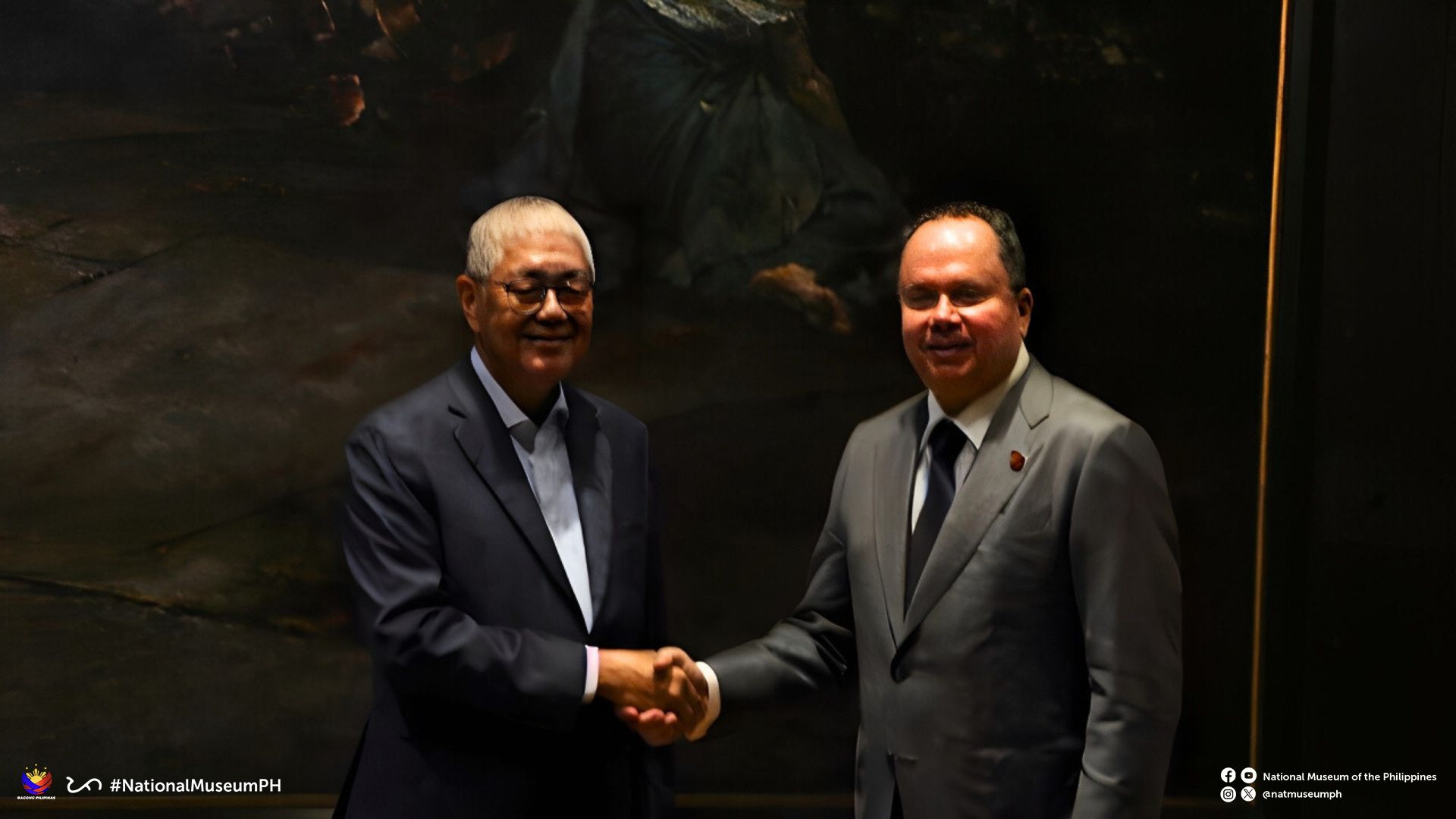

Chairman of NMP, Andoni Aboitiz

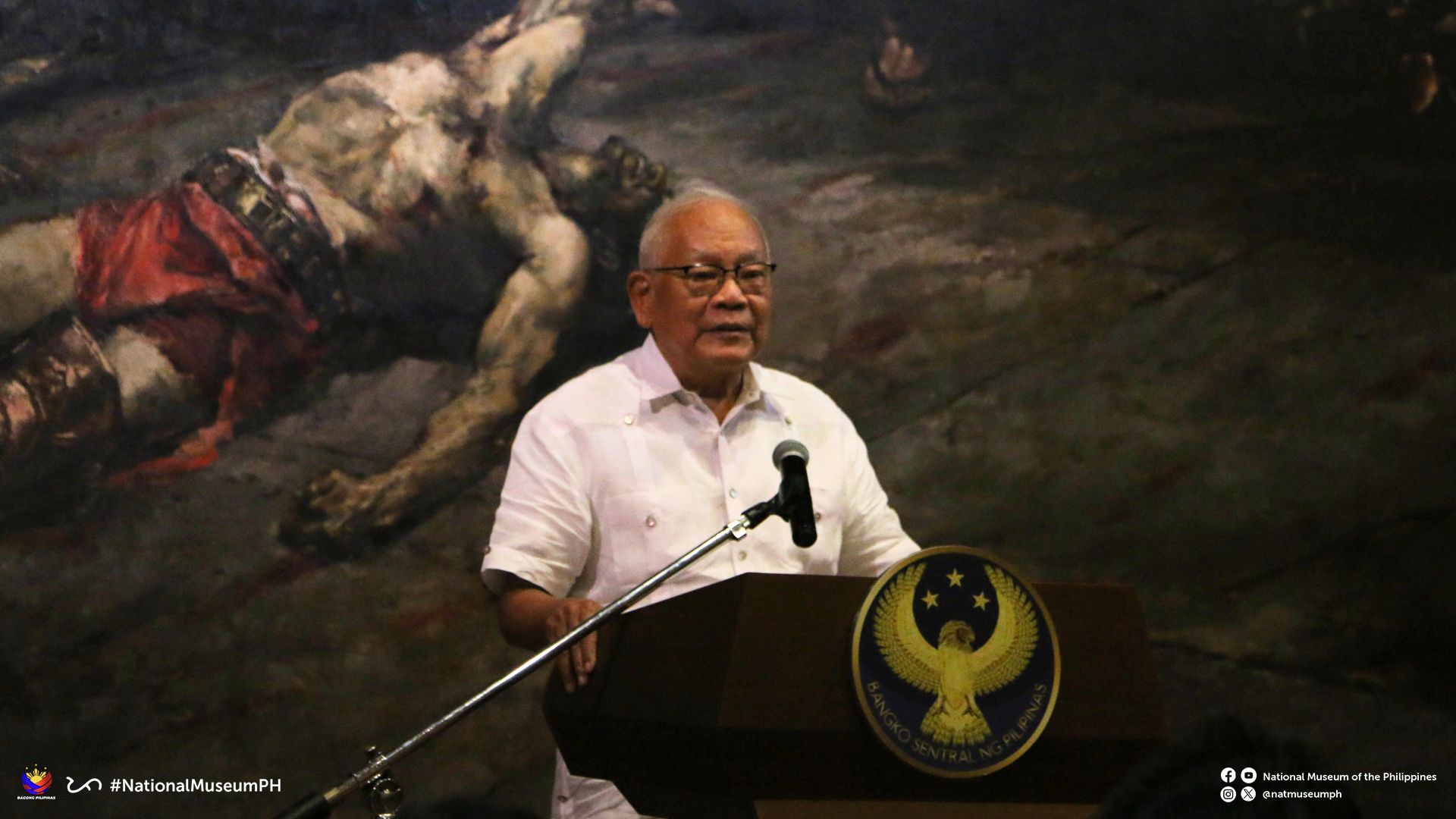

The BSP Governor Eli M. Remolona, Jr. and members of the Monetary Board joined the event, alongside former BSP Governor Amando M. Tetangco, Jr., Ms. Tess Espenilla (wife of the late Nestor A. Espenilla, Jr.), and the ever-graceful former Central Bank Governor Jaime C. Laya, who gave a short but enlightening talk about the BSP art collection.

From the NMP, Chairman Andoni Aboitiz, Director-General Jeremy Barns, and fellow trustees NCCA Chairman Victorino Mapa Manalo, Carlo Ebeo, and Jose Carlos Garcia-Campos also graced the occasion. Chairman Aboitiz expressed gratitude to the BSP for renewing its partnership, calling the exhibition a shining example of how financial institutions can also enrich our cultural wealth.

Former Governor of BSP Jaime Laya

Governor of BSP Eli M. Remona and Chairman of NMP Board Andoni Aboitiz

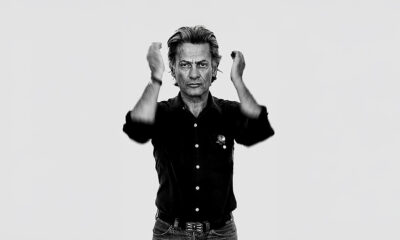

Artist Charlie Co

Before the official launch, a special media preview was held on 5 August, hosted by BSP Deputy Governor Bernadette Romulo-Puyat and DG Jeremy Barns. It gave lucky guests a sneak peek at the collection—because sometimes, even art likes to play “hard to get.”

The exhibition Kultura. Kapital. Kasalukuyan will run until November 2027 at Galleries XVIII and XIX, 3/F, National Museum of Fine Arts. Doors are open daily, 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM. So if you’re looking for something enriching that won’t hurt your wallet (admission is free!), this is your sign to visit. After all, the best kind of interest is cultural interest.

Monetary Board of the BSP, Walter C. Wassmer

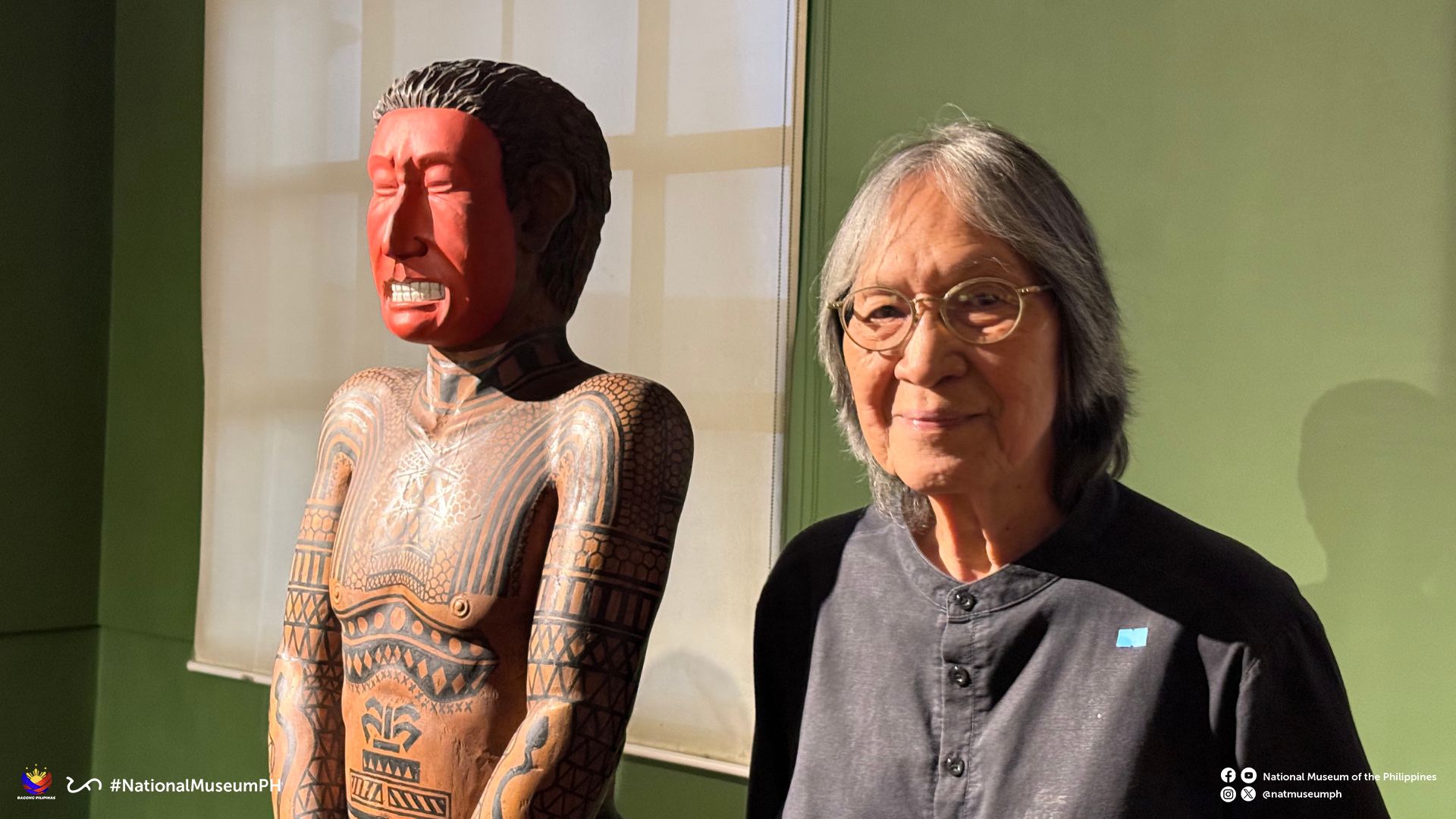

Luis Yee, Jr. aka ‘Junyee’ The Artist beside his Sculpture

Arvin Manuel Villalon, Acting Deputy Director General for Museums, NMP with Ms. Daphne Osena Paez

Arts & Culture

Asia’s Fashion Czar I Knew as Tito Pitoy; Remembrance of a Friendship Beyond Fashion with Designer Jose R. Moreno

by Jose Carlos G. Campos, Board of Trustees National Museum of the Philippines

My childhood encounter with the famous Pitoy Moreno happened when I was eight years old. My maternal grandmother, Leonila D. Garcia, the former First Lady of the Philippines, and my mother, Linda G. Campos, along with my Dimataga aunts, brought me to his legendary atelier on General Malvar Street in Malate, Manila. These were the unhurried years of the 1970s.

As we approached the atelier, I was enchanted by its fine appointments. The cerulean blue and canary yellow striped canopies shaded tall bay windows draped in fine lace—no signage needed, the designer’s elegance spoke for itself. Inside, we were led to a hallway adorned with Art Deco wooden filigree, and there was Pitoy Moreno himself waiting with open arms—”Kamusta na, Inday and Baby Linda,” as he fondly called Lola and Mommy.

“Ahhh Pitoy, it’s been a while,” Lola spoke with joy.

“Oh eto, may kasal na naman,” my mom teasingly smiled.

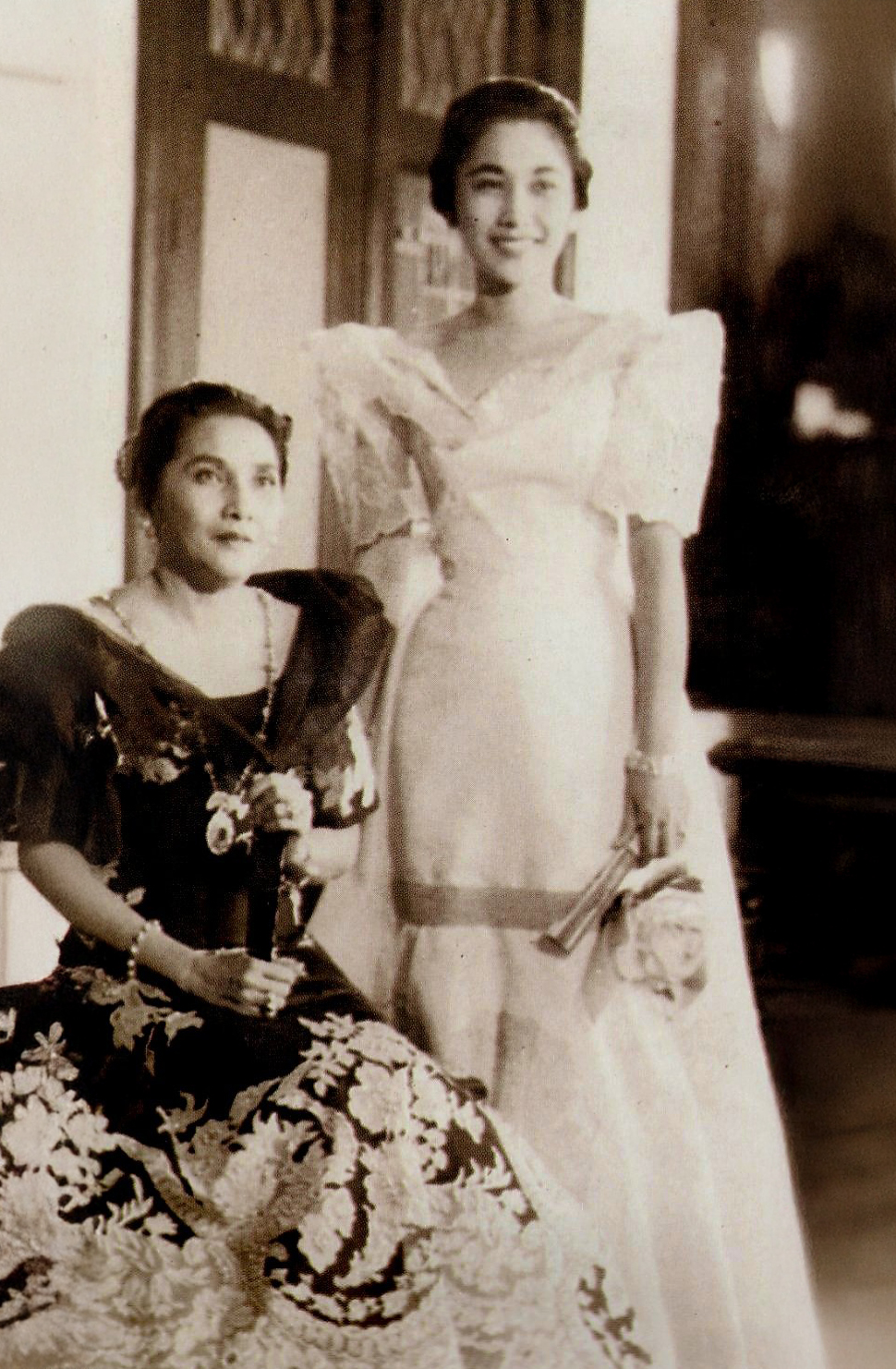

Linda Garcia Campos and Pitoy Moreno’s friendship started when they were students in the University of the Philippines in Diliman.

When Dame Margot Fonteyn came for a visit to Manila, Pitoy Moreno dressed her up for an occasion.

We had entered a world of beauty—porcelain figurines, ancient earthenware and pre-colonial relics. It was like stepping into a looking glass, only Pitoy could have imagined.

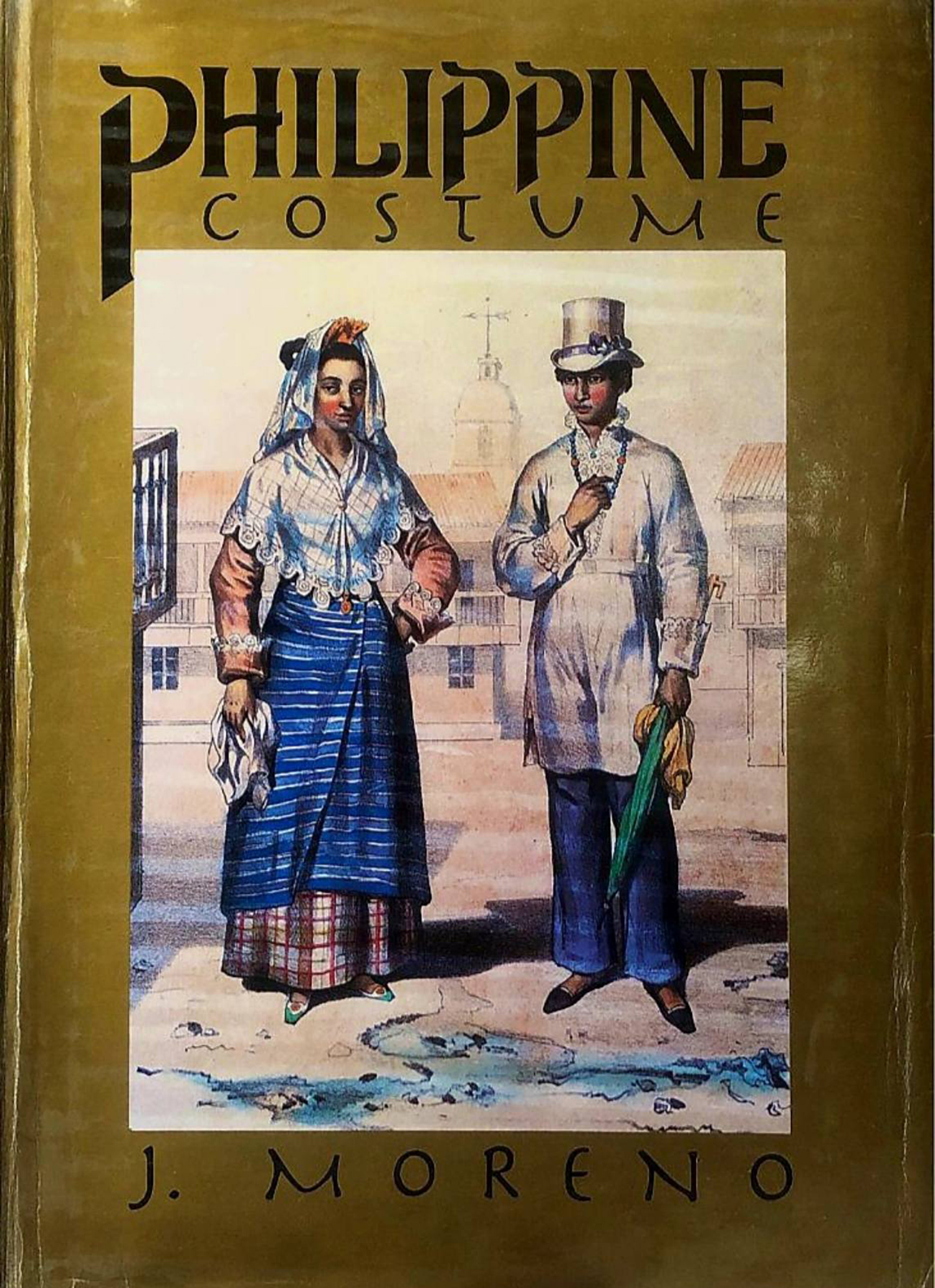

Destiny led me back years later when my mother Linda told me that Pitoy Moreno was working on his second book, Philippine Costume, and needed research material and editorial advice. At this point, around the 1990s, I was in between assignments—unsure of how a broadcasting graduate like me could possibly contribute to a fashion icon’s masterpiece. Fortunately, I agreed to the project.

Former First Lady Leonila D. Garcia and daughter Linda G. Campos in Malacañang Palace.

Returning to the designer’s atelier brought back a rush of pleasant memories. The gate opened, and there stood Pitoy Moreno, beaming as always.

“Come in, hijo. Let me show you what I have in mind—and call me Tito Pitoy, okay?”

He led me to his worktable.

“I want to publish a book that tells the story of Philippine fashion—from our pre-colonial roots to the present. A designer’s collection of images and heritage expressed in clothing.”

I was awestruck. “How can I help you?” I inquired.

“Did you know that your mother, Linda, was my barkada in the University of the Philippines in Diliman?” he grinned.

US President Dwight Eisenhower with First Lady Leonila Garcia and President Carlos Garcia in a state dinner at Malacañang Palace in Manila.

That friendship soon led to one of the proudest moments of the designer’s life. He had the opportunity to dress not only the First Lady Leonila D. Garcia but also President Carlos P. Garcia during his term. It was also during this time that the President of the United States, Dwight Eisenhower, came for an official visit to Manila. The designer was able to make clothes for the President, his daughter, and his staff.

“Eisenhower even asked for discounts on the barong Tagalog,” Tito Pitoy laughed.

Tito Pitoy then asked if I could find a terno he had made for my Lola, the former First Lady, which she wore for President Eisenhower’s state visit in 1960.

“How about her other ternos, dated from the 1920s to the 1960s?” I offered.

He lit up.

I scoured my Lola’s extensive closet—it felt like unearthing a legacy. Tucked behind layers of vintage ternos from countless fashion designers, I found that terno, which was photographed by Dick Baldovino along with other pieces for the book project. Once the project was finished and I myself had moved on, my bond with Tito Pitoy never wavered.

When my Lola passed away, he was deeply touched when I personally informed him of the sad news. Once, at the wake of former Vice President Salvador Laurel, he asked me to assist him in the placement of the medals in the chapel.

Philippine Costume by Jose Moreno is the designer’s collection of images and heritage expressed in clothing.

Tito Pitoy later invited me to his 80th birthday celebration—a dazzling Manila affair in 2012. During the evening’s festivities, he handed me a printed copy of Philippine Costume and added warmly,

“Thank you, hijo. I’ll call on you for the next one.”

The highlight of his career—and his most unforgettable moment—came during the Metro Magazine Gala fashion show: A Tribute to Pitoy Moreno, Fashion Icon. A collection of evening gowns spanning six decades—many of them unseen and tucked away in his atelier—were revealed that night. When the finale came, Tito Pitoy walked the stage, triumphant and waving to a sea of admirers. Longtime friends from the industry, society’s finest, and fashionistas rose from their seats and gave him a standing ovation.

It wasn’t just to celebrate his craft and ingenuity—it was to honor the man who brought elegance, history, and heart in every stitch.

-

Prime Target1 month ago

Prime Target1 month agoBee Urgello–Fashion Influencer and Designer’s Muse Goes on a Hiatus

-

Fashion1 month ago

Fashion1 month agoCloud Dancer: The Resonant Reset of 2026

-

Travel1 month ago

Travel1 month agoSunlight in Siquijor: Discovering the Landscape Shifts and Coastal Plains of this Mystical Island

-

Travel3 months ago

Travel3 months agoAutumn in Istanbul: Fellow Travellers Share Turkish Delights

-

The Scene3 months ago

The Scene3 months agoBe Fabulous: Dr. Fremont Base’s 50th Birthday Party Echoes the Disco-Glam Era

-

QuickFx2 months ago

QuickFx2 months agoIn Black and White: Photographer Richard Avedon Captures the Cultural Zeitgeist of His Era

-

Prime Target4 weeks ago

Prime Target4 weeks agoRod Malanao: Empowering the Growth of the Luxury Fashion Industry to Designing Knit Wear on the Side

-

QuickFx2 weeks ago

QuickFx2 weeks agoBright Young Things: Why Cecil Beaton Remains Vital in the World of Photography

You must be logged in to post a comment Login